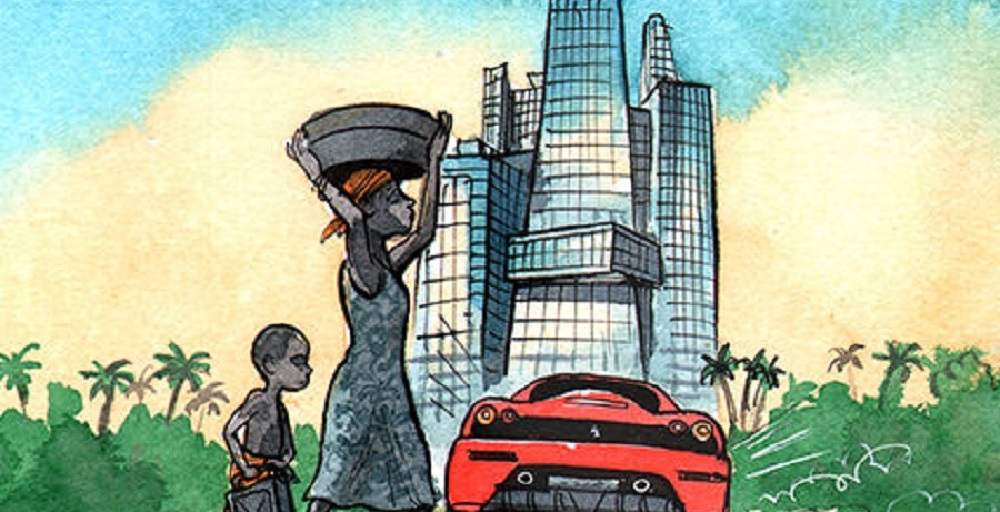

Teodoro Obiang, the president of Equatorial Guinea, and Teodorín, the most influential of his 42 recognised children, have expensive tastes. While most of his citizens live on less than $2 a day, the older Mr Obiang once shelled out $55 million for a Boeing 737 with gold-plated lavatory fittings. His son had at one point amassed $300m in assets, including 32 sports cars, a Malibu mansion and nearly $2m in Michael Jackson memorabilia, The Economist notes.

The past few years have been less kind to the Obiang clan. In 2014, the United States Department of Justice forced Teodorín Obiang to sell off a Ferrari, his Los Angeles abode and six life-size Michael Jackson statues in a money-laundering settlement. (He was allowed to keep one of the King of Pop’s crystal-encrusted gloves.) His father, who enjoys the distinction of being the longest-serving president in the world (36 years), has seen his pockets increasingly pinched as oil prices have crashed.

While prices were favourable the country boomed. According to the IMF, its GDP expanded by an average of almost 40% per year between 1996 and 2006. But little wealth trickled down to the population. Though its GDP per head is the highest in Africa, over three-quarters of its population lives below the World Bank’s poverty line. Government spending on education and health lags far behind the sub-Saharan African average. Tutu Alicante, the executive director of EG Justice, an advocacy group, compares visiting a public hospital to “signing your own death sentence”. Patients must bring their own sheets and share their rooms with rats.

Mr Obiang has instead channelled Equatorial Guinea’s petrodollars into grand projects such as Oyala, a new city he is building deep in the jungle. He hopes to move his capital there to avoid seaborne coup attempts, such as the one he suffered in 2009. The area currently consists of a new 450-room luxury hotel and a warren of empty buildings intended to become an international university.

Such endeavours are becoming increasingly difficult to fund. Declining oil production, coupled with lower prices, have led Equatorial Guinea’s economy to shrivel since 2013. Last year was especially grim: GDP shrank by an estimated 10.2%. The great majority of citizens never reaped the benefits of their country’s upturn, so their experience of its downturn has been muted, but work is getting scarcer.

Mr Obiang, who overthrew his uncle to become president, has a deplorable human-rights record; dissidents who anger him sometimes end up in prison where guards have been known to shock, beat and carve up their wards with knives. Nobody would be surprised if the economic crunch results in even greater repression. In January, two members of an opposition party, Convergence for Social Democracy, were arrested for the crime of handing out leaflets announcing a future meeting.

As the 73-year-old Mr Obiang becomes frailer, his sons, including the prodigal Teodorín, have begun jockeying to succeed him. But in November, when Equatorial Guinea is scheduled to hold a presidential election, there is no doubt about who will prevail—whatever the price of oil.