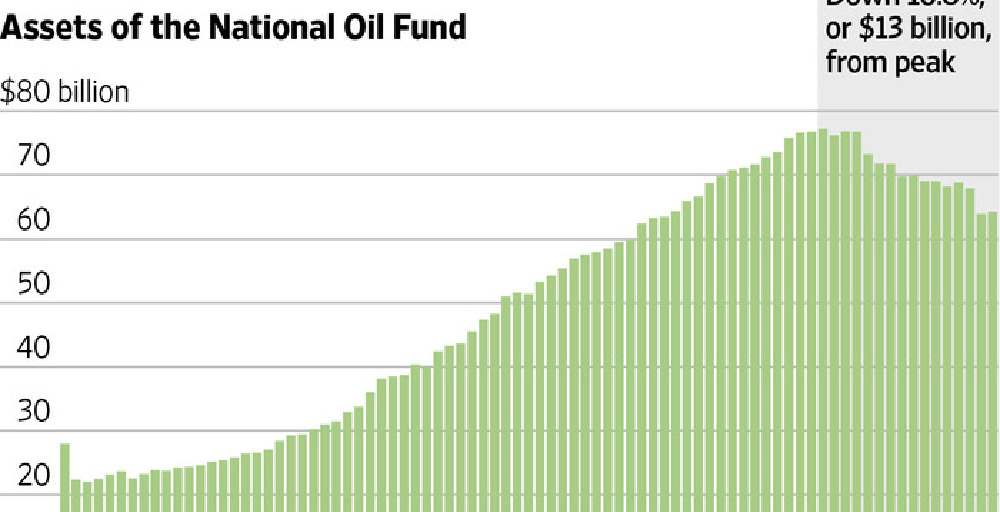

Kazakhstan’s $64 billion oil fund could run out of money within six or seven years as slumping oil prices cut revenue and the government spends its savings, a central-bank official said to the reporter of The Wall Street Journal.

The so-called National Fund has fallen 17% from its peak of $77 billion in August 2014. The government is drawing as much as $9.5 billion a year from it for spending. Kazakh politicians and the central bank need to cut spending, boost tax collection and invest the fund in higher-yielding assets such as private equity, according to Berik Otemurat, chief executive of the National Investment Corp., a unit of the central bank created in 2012.

“We are eating up the National Fund,” Mr. Otemurat said in an interview. “The money we have been lucky to accumulate is the only money we have to capitalize on. I think the government needs to focus on the National Fund’s investment management.”

Trillions of dollars of state savings in oil-rich nations from Kazakhstan to Saudi Arabia are under threat as governments that grew accustomed to high oil revenues scramble for cash. The International Monetary Fund is advising nations from Asia, Africa, Latin America and the Middle East to devise sovereign-asset and liability-management plans that will involve a combination of asset sales, budget cuts and domestic and international borrowing to stabilize public finances.

“They need to act quickly,” Michael Papaioannou, an IMF official who has advised Kazakhstan on managing its reserves, said in an interview. “If the current situation continues, the assets of the sovereign-wealth funds are going to be disappearing fairly quickly.”

The National Fund had an average annual return of 1.96% in the last five years, just a fifth of the 9.6% average for a group of sovereign-wealth funds including those of Norway, Singapore and South Korea, according to the National Investment Corp. document. The fund has invested 86% of its money in bonds, compared with a 16% average for the group of sovereign-wealth funds, the document said.

“If on $100 billion we can make $5 billion or $6 billion a year in income, it helps support annual government spending,” Mr. Otemurat said. “We have to disclose our returns, how we invest, who the managers are, inflows, outflows and spending. It isn’t the case today, and it is difficult.”

The profit-sharing agreements for Kazakhstan’s oil fields—the source of the money in the National Fund—aren’t publicly available, and the fund doesn’t have its own website, he said. The 35-year-old executive said he sees himself as part of a new generation of Kazakhs with international experience that isn’t represented in the country’s political leadership.

Photo: www.wsj.com